John Wilson

(1906-1979)

With the death of John Wilson last month in Willowdale, Ontario, so passed from the piping scene one of the great characters of this century.

So wrote Seamus MacNeill in the Piping Times in November, 1979, encapsulating what all who knew John Wilson would most remember most about him.

He was born in Edinburgh in 1906 and began learning the pipes in 1915 from Pipe Major Robert Thomson of the Argyll & Sutherland Highlanders at Edinburgh Castle. He progressed quickly and in 1917 was sent for tuition to Roderick Campbell, who won the Gold Medal at Oban in 1908 and was one of the leading composers and teachers of the day. They developed a most productive teacher-pupil relationship and were good friends until Campbell died in 1937.

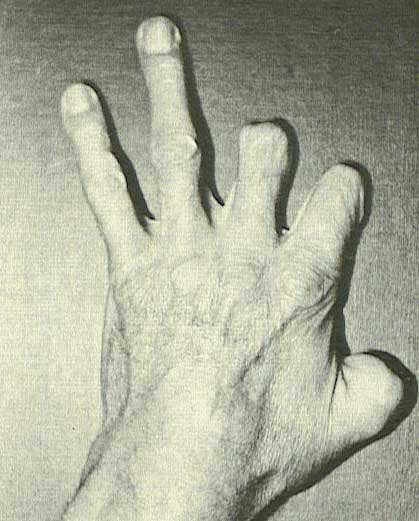

On the eve of Armistice Day in 1918 he was enjoying the usual playful explorations of a 12-year-old when he found and accidentally ignited the detonator of a stray hand grenade and blew off the major parts of the thumb and first two fingers of his left hand. Only short stumps remained extending from the knuckle of his hand. The majority of young pipers might have abandoned the pipes, but no so the young John Wilson, who displayed the perseverance that would be a guiding trait throughout his life. He went back to the practice chanter and relearn his fingering. By 1921 he was winning the major amateur prizes again.

In 1924, still in his teens, he began capturing the top prizes. He won the Marches at Oban that year, and the following year the Gold Medal at Inverness. In 1927 he won the Gold Medal at Oban and the Strathspeys and Reels at Oban and Inverness.

His life revolved around piping, and he took on a variety of jobs, from accounting clerk to male model, leaving as required to spend the summers playing the Games circuit. He was a professional piper, achieving sustained success throughout the 1920s and ’30s against the likes of Robert Reid, R. U. Brown, Willie Ross, J. B. Robertson and Malcolm R. MacPherson. It was a Golden Age of piping, and John Wilson was one of the great pipers of the age. During what he called his peak year in 1936, he received 70 prizes in 72 events, winning first in 35 of them and second in 24. Two of these firsts included the Clasp at Inverness and the Former Winners’ March, Strathspey and Reel at Oban.

By this time he was flourishing as a composer, and his tunes were gaining in popularity. In 1937 he published his first book of bagpipe music containing original compositions not just by himself, but by John MacColl, G. S. McLennan, Roderick Campbell, Peter MacLeod Jr., and Ian C. Cameron. A second volume would appear in 1957 and a third in 1967. To this day the three John Wilson collections rank in stature alongside those of Willie Ross and Donald MacLeod.

He volunteered for service in World War II and was appointed Pipe Major of the 4th Battalion Cameron Highlanders, the Inverness-shire Territorials. Of this appointment, The Camerons’ Caber Feidh Collection notes:

But having no previous military experience,and being a man of strong character and decided views, he was perhaps not the happiest choice for such a post in a close knit unit of entirely Highland composition which included several good players of long Territorial service. In due course he was appointed personal piper to the General Officer commanding the 51st Highland Division, Major General Victor Fortune of the Black Watch and the Seaforth Highlanders.

In June of 1940 his life changed forever when he and the unit, including General Fortune, was captured by the German army at St. Valery, France. He would spend the next five years in prisoner-of-war camps, cut off from friends, family and piping, until liberated by U.S. forces in April of 1945.

He would not compete again until 1948, and the next year his life would bring about great change again when, on the prompting of his friend George Duncan, he decided to immigrate to Canada.

One of his first acquaintances was Pipe Major John Reid, who had brought him to Oshawa, Ontario, home of the huge General Motors plants. While P/M Reid didn’t have a job for him, he did have a daughter. John was smitten with Margaret Reid immediately. They would marry in 1950 and eventually have two sons.

With work scarce in Oshawa due to a temporary plant shutdown, John settled first in Hamilton, Ontario, joining the pipe band of the Argyll & Sutherland Highlanders under Pipe Major J. K. Carins. Cairns retired the next year, and Wilson was named Pipe Major. After an eventful trip to Scotland in 1951, John decided pipe majoring was not for him and he left the band and moved with Margaret to Toronto.

He had been competing at the Games since he arrived, and shortly after arriving in Toronto he began offering Saturday piping classes at Fort York Armoury. These lessons, along with private teaching in his home, would dramatically change the face of piping in Ontario over the next 25 years. Reay MacKay, Billy Gilmour, Bill Livingstone, Bob Worrall, Gail Brown, Michael Grey and many others – all owed much of their piping success to the rigorous teaching of John Wilson in Toronto. His exacting standards as a teacher and judge raised the level of technique and instruments in Ontario to unparalleled heights. It was without doubt due to the influence of John Wilson that Ontario pipers earned reputations in Scotland in the 1970s and 1980s for impeccable technique, flawless performances and strong, steady pipes.

During these years his health was an ongoing issue. He suffered a heart attack in 1955 and in 1963 cancer was discovered in his left lung and the lung was removed. Despite these difficulties he judged and taught relentlessly, and even returned to the Boards at the Brockville games in 1972 at the age of 66, earning seconds in the Strathspey and Reel and the Jig against the leading Ontario players of the time.

John Wilson cut a larger-than-life figure through all his days. His quick wit and unrelenting determination to say and stand up for what he thought did not endear him to all, but certainly earned him respect and a reputation for integrity given to few others. His frequent articles and letters the Piper and Dancer Bulletin throughout his time in Canada pointed out shortcomings in the piping community besides preserving a cross-section of the piping world at the time. His 1978 book, A Professional Piper in Peace and War, is an engaging, forthright and often humourous autobiography that remains an important record of the Scottish piping scene during the early part of the 20th century.

His extensive legacy of tunes belong with the best in pipe music: the slow airs “Loch Rannoch,” and “Leaving Lochboisdale,” his reel “Tom Kettles,” and his six-part setting of “Loch Carron,” his now classic four-part setting of “The Irish Washerwoman,” the hornpipes “Bobbie Cuthbertson” and “St. Valery,” and a string of great old-style jigs like “Sandy Thomson,” “Angus MacPherson,” John Grieve,” “Before Kirkmichael Games” and many more.

He died from lung cancer in Toronto on November 6, 1979. He left his body to science and there was no memorial service. Seumas MacNeill’s Piping Times tribute summed up a character that few who knew will ever forget:

His contribution to piping in Ontario can not be over-estimated. He brought with him the genuine music of Scotland, the respect for technical accuracy, and the drive for competitive success which has inspired a whole generation of Canadian pipers. He strove constantly for the improvement of the status of a piper, and if in so doing he rubbed many people the wrong way it was no more than they deserved. He was intolerant of inefficiency, selfishness and hypocrisy. He did not suffer fools gladly; indeed he did not suffer them at all. He could be kind in his comments to pipers, pointing out the good as well as the bad in their performances. Be he had no mercy on incompetent judges.

His respect for his fellow professionals was high, and while he felt that it was always his duty to try to win, he never considered that his victory should be achieved by decrying the opposition. His opinion was often sought by pipers, and even when not sought was freely given, especially in his many writings in the piping journals. Often his opinion was not the one expected, but it was always given with perfect honesty and usually without thought of political repercussions.

-JM, April 2007

-with notes and photos from ‘A Professional Piper in Peace and War’, by John Wilson, Piping Times,December 1979, and ‘The Cabar Feidh Collection, Pipe Music of the Queen’s Own Highlanders’ (Seaforth and Camerons).

6 Comments

I started lessons with John Wilson and the A & SH of C in 1963. John would lay one $5.00 bill for each new student, the cost of a practice chanter. John held a steel edge ruler as you played for him and when a mistake was made he would rap those fingers – too many mistakes meant you didn’t practice enough, and he would grab your chanter and firing a five at you he would tell you to leave!! The class of around 15 students quickly dropped to 2, which shocked the Pipe Major, George Henderson who asked what happened to his class?? John answered that the PM didn’t need the rest, just these two!! Looking back on it I can see his quick way of weeding out the ones that didn’t have the commitment and focus on the ones that did. Even as a kid of 12 he became a Bagpipe Hero to me!!

I have a glorious story about P/M Wilson which must be told. Please send me an email address which I can use to send it to you. Piper Dich Blair

info@pipetunes.ca

Or just tell the story here! JM